In the last few years, the European Commission has been very active in the corporate tax field, producing a number of legislative proposals. The most important one was, arguably, the Directive on Minimum Effective Tax Rate, which was approved in Council in December 2022. Member States were given until the 31 December 2023 to incorporate the provisions of the new Directive into domestic law. The provisions of this Directive were analysed in a previous newsletter.

In this newsletter, we examine the legislative tax proposals which are still in the pipelines. These are the proposed Unshell Directive, the proposed Directive on Faster and Safer Relief of Excess Withholding Taxes, the proposed BEFIT Directive (Business in Europe: Framework for Income Taxation), the proposed Transfer Pricing Directive and the proposed Directive on Head Office Tax.

THE UNSHELL PROPOSAL

The Unshell proposal was first published as a draft Directive in December 2021. The aim of this proposal was to establish transparency standards around the use of shell entities to enable tax authorities to detect abuse more easily. There is a filtering system (gateways) comprising of several substance indicators. Undertakings will need to show that they satisfy the substance indicators, otherwise they will be presumed to be “shells”. Such a finding could lead to penalties, a denial of a tax residency certificate and unavailability of exemptions under the Parent-Subsidiary and Interest and Royalties Directive.

If adopted as proposed, the Unshell proposal will introduce a heavy compliance burden of reporting, preparation of rebuttals and appeals, not just for MNEs but also for smaller undertakings involved in cross-border transactions. Although the European Commission was expected to publish a revised version of this draft Directive in 2023 to meet the concerns of some stakeholders, this has not happened.

If this proposal is adopted, Cyprus and other traditional holding company jurisdictions are likely to be affected. Of course, much would depend on the gateways and substance indicators that are eventually approved. In any case, advisors would need to assess which undertakings may come within the scope of the rules, whether they can benefit from any carve-outs and how they can ensure they remain low-risk in order to be exempt. If reporting of minimum substance is inevitable, then diligent preparation of documentary evidence will be crucial to ensure the rebuttal of the presumption of a shell.

THE FASTER DIRECTIVE

The Directive on Faster and Safer Relief of Excess Withholding Taxes (FASTER Directive) was proposed by the Commission in June 2023. This proposed Directive is aimed at streamlining the withholding tax reimbursement process making withholding tax procedures in the EU more efficient and secure for investors, financial intermediaries and tax administrations. The Directive also seeks to remove obstacles to cross-border investment and to curb certain abuses.

Three options are set out in the Commission’s proposal.

Under the first option, Member States would continue to apply their current systems (i.e. relief at source and/or refund procedures) but would introduce a common digital tax residence certificate (eTRC) with a common content and format which would be issued/verified in a digital way by all Member States. There would also be a common reporting standard to increase transparency as every financial intermediary throughout the financial chain would report a defined set of information to the source Member State. It would be accompanied by standardised due diligence procedures, liability rules and common refund forms to be filed on behalf of clients/taxpayers using automation.

This second option builds on the elements included in the first option but makes it compulsory for Member States to establish a system of relief at source at the moment of payment that allows for the application of reduced rates under a tax treaty or domestic rules. Under this option, tax administrations would have to monitor the taxes due after the payment takes place.

The third option also builds on the first option, with the added requirement that Member States applying a refund system should ensure that the refund is handled within a pre-defined timeframe, through the Quick Refund System. Member States can introduce or continue to implement a relief at source system.

Of all the options, the third option is considered (by the Commission) to be the preferred option. While the second option would lead to even higher cost savings for investors, the third option enables Member States to retain an ex-ante control over refund requests. This is likely to be more politically feasible in all Member States.

Even though Cyprus does not, in general, levy withholding taxes other than on certain outbound payments if the recipient is a company resident in a jurisdiction featured in the EU’s list of non-cooperative jurisdictions, the proposed Directive is likely to have an impact on the Cyprus tax system. The development of a harmonised digital certificate of residence will help speed up the procedures for relief of excess withholding taxes from other jurisdictions.

Of course, Member State tax administrations will need to be equipped with tools to deal with the relief/refund procedures in a secure and timely manner and to train the relevant staff supervising such tools.

BEFIT

In September 2023, the Commission published the much-awaited BEFIT Directive (Business in Europe: Framework for Income Taxation). This proposal replaces the previously proposed Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base but the overall aim is the same: to set out a new framework of tax rules to help all companies in a group to determine their tax base on the basis of common rules. The new rules will be mandatory for groups operating in the EU with an annual combined revenue of at least €750 million. Smaller groups may choose to opt in.

All members of the same group (the ‘BEFIT group’) will calculate their tax base in accordance with a common set of rules applied to their already prepared financial accounting statements. The tax bases of all members of the group will then be aggregated into one single tax base, with losses automatically set off against cross-border profits.

Tax returns will be filed both at the level of the filing entity and each group member. Member State authority representatives (the ‘BEFIT team’) will assess and agree on the content and treatment of the BEFIT Information Return. Each Member State where the multinational group is present will be allocated a percentage of the aggregated tax base under a transitional formula. Very importantly also, each Member State can then adjust their allocated tax base according to their own national rules, calculate the profits, and tax at their national corporate tax rate.

BEFIT is expected to reduce tax compliance costs for large businesses. However, a close reading of the proposal suggests that there are some differences with Pillar 2 (and the Directive on Minimum Effective Tax Rate) which is likely to increase the compliance burden of in-scope groups.

In addition, although the BEFIT’s procedural rules were meant to provide a one-stop shop for corporate taxation of MNEs, quite the opposite, they seem to lead to a two-tier compliance mechanism. There is the double filing of returns, but also the possibility of parallel operation of double (and multiple) audits in the Member States involved. (See the IBFD Taskforce’s assessment of the BEFIT.) This is highly unsatisfactory.

Furthermore, the ability to make national adjustments to the allocated part is likely to give rise to tax (base) competition, which to an extent, defeats the objective of having a common tax base.

Whilst there are likely to be very few (if any) Cypriot in-scope groups, nevertheless, the existence of an additional tax base could be attractive to smaller groups that might choose to opt in. Therefore, if the BEFIT Directive is adopted, advisors should assess whether the new tax base is more beneficial than the Cyprus tax base for any Cypriot group with non-resident subsidiaries, and whether a transition to the new system should be encouraged.

TRANSFER PRICING DIRECTIVE

The draft Transfer Pricing Directive was proposed at the same time as the BEFIT proposal, in September 2023. This Directive aims to harmonize transfer pricing rules within the EU, in order to ensure a common approach to transfer pricing problems. As stated in the preamble (page 2), the “proposal aims at simplifying tax rules through increasing tax certainty for businesses in the EU, thereby reducing the risk of litigation and double taxation and the corresponding compliance costs and thus improve competitiveness and efficiency of the Single Market”.

This objective is achieved by incorporating the arm’s length principle into EU law, harmonizing the key transfer pricing rules, clarifying the role and status of the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines and creating the possibility to establish common binding rules on specific transfer pricing issues.

The draft Directive contains a common definition of associated enterprises (and therefore the transactions covered). It encompasses a person (legal or natural) who is related to another person in any of the following ways:

- significant influence on their management;

- a holding of over 25% of their voting rights;

- a direct or indirect ownership of over 25% of their capital; or

- a right to over 25% of their profits.

It is clarified that a permanent establishment is an associated enterprise. This is not always the case under national tax laws.

The draft Directive also adopts key elements of the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines such as the accurate delineation of transactions undertaken, comparability analysis and the five recognised OECD Transfer Pricing methods.

Very importantly, the draft Directive provides for mechanisms to enable corresponding and compensating adjustments. There is a process for applying corresponding adjustments on cross-border transactions within the EU that aims at resolving, within 180 days, any double taxation that follows from transfer pricing adjustments made by an EU Member State. A framework is also introduced for compensating adjustments, which must be recognised by Member States.

In order to ensure a common application of the arm’s length principle it is expressly stated that the latest version of the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines will be binding when applying the arm’s length principle in Member States.

Broadly, the common definition of associated enterprises is very welcome, as this concept is not harmonised across Member States. However, the 25% threshold is different from the criteria set out in the BEFIT Directive and the Directive on Minimum Effective Tax Rate. This is likely to cause difficulties in coordinating the various rules.

In addition, the 180 days fast-track process is very attractive, as it will help speed up the resolution of disputes. The framework introduced for compensating adjustments is also very important as not all Member States accept compensating adjustments which can lead to double taxation.

If adopted, this Directive will have an impact on Cyprus transfer pricing rules, mostly in the context of streamlining corresponding adjustments. From a literal reading of Art 33(1) and (5) of Cyprus’ Income Tax Law, it would seem that only upwards compensating adjustments are accepted by the Cyprus tax authorities – unless of course there is a tax treaty in place which provides for upwards and downwards adjustments. The current practice suggests that the Cyprus tax authorities are unwilling to allow downwards adjustments. Also, the law is silent on compensating adjustments, but again it would seem that on the basis of a literal reading of Art 33(1) and (5), only if the compensating adjustments would result in an upward adjustment will they be accepted by the Cyprus tax authorities. If the Directive is adopted, these practices will have to change.

As for the other provisions of the Transfer Pricing Directive, whilst Cyprus now broadly follows the OECD’s Transfer Pricing Guidelines, its transfer pricing regime is a rather new regime. Therefore, a harmonised EU regime will likely have spillover effects as regards the interpretation and application of the newly adopted concepts.

HEAD OFFICE TAXATION DIRECTIVE

Under the new Head Office Taxation Directive (HOT Directive), qualifying SMEs with permanent establishments in other Member States will be able to calculate their tax liability based only on the tax rules of the Member State of their head office.

There are a number of conditions determining eligibility of SMEs, which are scattered in the proposal. Broadly, the proposed regime will only be open to EU tax resident companies (of a form listed in the Annex) with EU permanent establishments. Non-EU permanent establishments are excluded from the scope of the Directive.

There are also size-related requirements. In order for companies to be eligible, they must not exceed at least two of the following three criteria, on a yearly basis: (i) total balance sheet of EUR 20 million; (ii) net turnover of EUR 40 million; (iii) average number of employees of 250.

The draft Directive excludes from the scope of the regime SMEs which are part of a consolidated group for financial accounting purposes in accordance with Directive 2013/34/EU and constitute an autonomous enterprise. There is some uncertainty in this eligibility condition, which is likely to be addressed in a revised draft.

SMEs would only file one single tax return with the head office Member State. This return would then be shared with other Member States where the permanent establishments are located. Collection will take place at the Member State of the head office, but revenues will be shared with the tax authorities of each permanent establishment.

Audits, appeals and dispute resolution procedures will remain domestic and in accordance with the procedural rules of the respective Member State. Joint audits may also be requested by tax authorities. The proposed Directive will amend the Directive on Administrative Cooperation (the DAC) to enable the exchange of information between Member States for the proper functioning of the Head Office Tax Directive.

If a qualifying SME opts into this regime, then it must apply the rules for a period of five fiscal years, which can be renewed. The regime would cease to apply before the expiration of the five-year term if either (i) the SME transfers its tax residence out of the head office Member State or (ii) the joint turnover of its PEs exceeded an amount equal to triple the turnover of the head office for the last two fiscal years.

Broadly, the proposed Directive will create a one-stop-shop regime whereby the tax filing, tax assessments and collections for permanent establishments will be dealt with through the tax authority in the Member State of the head office.

The fact that the tax base of permanent establishments will be calculated according to the tax rules of the head office might generate tax competition. Cyprus and other Member States will strive to have attractive head office tax provisions in order to attract qualifying SMEs. Of course, this will also lead to an increase in the workload of the Cyprus tax authorities, as they would act as a one-stop-shop, dealing with the tax filing and assessment of the various components of the SME, as well as the collection and payment of revenues to other tax authorities. Therefore, adequate resources will need to be devoted to the Cyprus tax authorities, in order to be able to perform their role in the context of this proposed Directive.

It should be pointed out that the proposed Directive does not directly impact Cyprus’ transfer pricing rules. The proposed rules will simply enable permanent establishments of qualifying SMEs to have their profits calculated according to the tax rules of the Member State of the head office. Therefore, assuming we have a qualifying Cyprus head office with Greek permanent establishments, the Cyprus tax rules will apply to determine how the profits of the Greek permanent establishments will be taxed. Those taxable profits will be subject to the Greek tax rates. However, the prior question of what profits will be attributed to the Greek permanent establishments (which will then be subject to the Cyprus tax rules) is most likely to be determined by Greek tax rules on profit attribution to permanent establishments. Unfortunately, this important point is not clear in the proposed Directive and is likely to give rise to disputes.

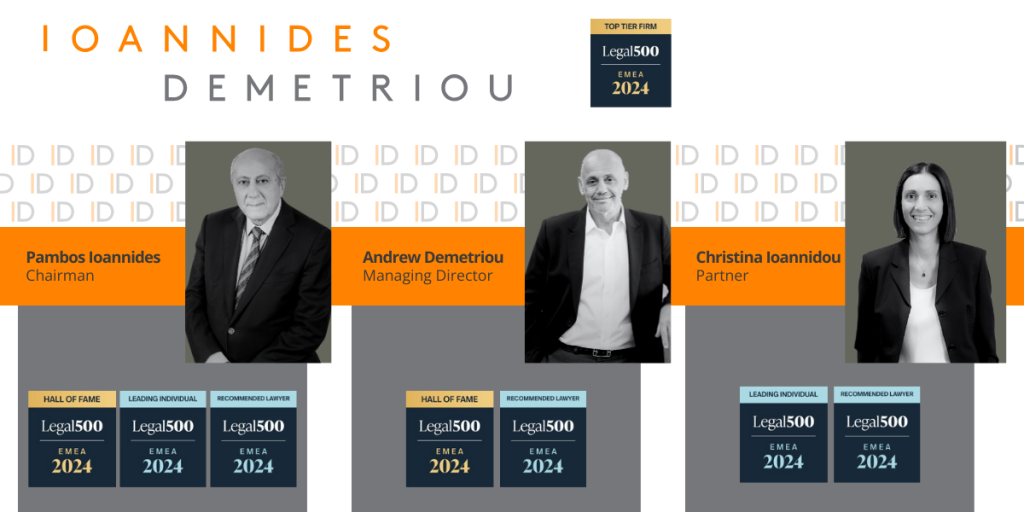

For information on any of the issues raised in this newsletter, please get in touch with us.